A conversation with Bose legend Dan Gauger

On the past, present, and future of Bose noise-cancelling headphones

Please note: In September 2022, Dan Gauger retired after 42 years at Bose. The final project he worked on was the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds II — a product he told us that he's dreamed of "for 15 years." To honor Dan's legendary career, we've preserved this interview from 2020.

Sometimes it seems like Bose noise-cancelling headphones have always been around. They've become ubiquitous in airports, offices, as well as in our collective memory. And they're so effective at silencing loud noises that many reviewers — myself included — fall into the lazy trap of calling them "magic."

Bose Distinguished Engineer Dan Gauger can tell you both of those things aren't true.

Dan celebrated his 40th anniverary at Bose in 2020. He's one of two engineers (along with Roman Sapiejewski) who founded and developed their noise-cancelling headphones business and technology.

Dan joined Bose in 1980 to help build their legendary noise-cancelling headphone business from scratch, and has been there ever since. So he knows that you can't credit their success to some sort of mysticism or alchemy. Instead, it takes a lot of know-how, problem-solving, and teamwork to create products like the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds — which cancel noise better than any other in-ear headphone I’ve ever tried.

(Since this interview was released, Bose has also released their new flagship Bose QuietComfort Ultra over-ear headphones.)

Connecting with a pioneer of noise cancellation

At one point last year, I planned to fly from Virginia to Massachussets — coddled in silence by a set of QuietComfort over-ears — so I could interview Dan at the Bose Corporate headquarters in Framingham (about 30 miles west of Boston). But of course, 2020 happened. So instead, we connected via Microsoft Teams earlier this fall.

After 40 years of battling noise at Bose, there's no telling how many times Dan has made the trip to the famed "Mountain" where the company is headquartered. But this was only the second time in six months he had been to his office.

The Bose Corporate Center is perched on top of "The Mountain" in Framingham, MA.

So as I sat in my home office, Dan basically had an entire floor of the building to himself. But what the place lacked in people, it made up for in memories. Dan and I had a long, wide-ranging conversation, often punctuated by an old photograph or early prototype headphones that Dan dug out of his desk drawers.

I had just auditioned the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds for about two weeks, so I was eager to discuss them. And that led to many other topics, including the history of Bose noise-cancelling headphones, working directly with Dr. Bose, the company's design philosophy, and what the future holds for noise cancellation.

Below are edited excerpts from that conversation, along with some choice video clips:

Jeff Miller: So you just recently celebrated your 40th year at Bose?

Dan: Yep, in July. My 40th anniversary at Bose.

I’m guessing you weren’t able to properly celebrate that milestone?

Lots of emails from colleagues around the company and messages. There was sort of a celebratory booklet put together that people put comments in. But obviously no sort of gathering. This is a very, very odd time.

I caught up with Dan in the (almost empty) Bose headquarters from my home office in Virginia.

Yeah I’ve only been to Crutchfield HQ three times since March.

Yeah, and it is challenging with our headphone work. Because a big part of what we do is creating prototypes and measuring them on people. So it’s very, very difficult to coordinate all that.

Release of the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds

A few weeks before our chat, I received a prototype of the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds — the first true wireless headphones with real-deal Bose noise cancellation. I’ve tried some earbuds in the past that were average to very good at canceling noise, but I always like to set proper expectations.

These Bose earbuds were the first in-ears that I'd say could rival the noise cancellation in over-ear headphones. When I mowed the grass, I could turn on the active noise cancellation and almost completely knock out the sound of the mower. I didn’t even have to turn on any music!

Jeff: Let’s jump right into the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds. Because spoiler alert — they are very good.

Dan: (Laughs.) I agree. I’ll pass that along to the engineers who did the hard work.

The Bose QuietComfort Earbuds offer precise control over the level of noise cancellation via the Bose Music companion app.

What are the design challenges for noise cancellation in the in-ear form-factor vs over-ears?

The core challenge of any noise-canceling headphone is balancing the active cancellation, the passive, and of course the comfort. And with an around-ear headphone — like the Bose Noise cancelling 700 headphones I’m wearing now — that passive [noise cancellation] is easier. But with an earbud, you don’t have as much air trapped underneath it. And that hurts the passive attenuation unless you really seal hard into the ear canal….which isn’t comfortable!

Yeah, I always call Bose earbuds, "in-ears for people who don't like in-ears," since they don't go in as deeply and kind of rest inside the ear [thanks to the StayHear Max ear tips].

It's a really interesting challenge to come up with an ear tip that is comfortable and seals well, yet still allows [the active noise circuitry and processing] to sense what’s happening in the ear canal…balancing those things out is uniquely interesting in earbuds.

Bose designed the QC Earbuds to better conform to your ears. The result is a secure, comfortable fit that avoids pressure points and makes a proper seal for noise isolation.

Does the fact that they are true wireless headphones introduce any other challenges?

Indirectly. Because you're competing with other features like the Bluetooth radio, both for space and battery power, in a small earbud. That's the key thing — competition for limited resources.

VIDEO: What was the design goal for these earbuds?

I asked Dan what Bose set out to accomplish with the QuietComfort Earbuds, and I thought his answer was particularly interesting. Quick note: I picked up on some of Dan's shorthand in this conversation. When he talks about a headphone or headset's "performance," that almost always means how well it cancels noise.

The history of Bose noise-cancelling headphones

The first Bose QuietComfort noise-cancelling headphones debuted in the year 2000 — and arrived at Crutchfield in early 2001. A long, interesting path with many twists and turns led to that momentous release.

1978 — Dr. Bose takes a flight

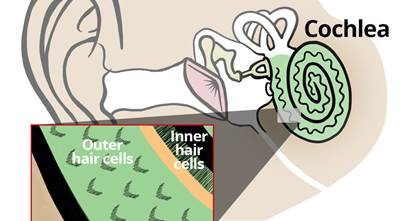

Noise-canceling headphones have built-in circuitry that counteracts exterior sound by emitting an out-of-phase sound wave. This wave effectively cancels out the incoming sound. “You have to match every peak in the noise,” said Dan.

This concept of positive phase vs negative phase wasn’t necessarily new in 1978, but it hadn’t been seriously considered for headphones. Then Dr. Amar Bose got on a plane.

Bose founder Dr. Amar Bose was a brilliant inventor and iconic figure in the world of audio — as well as a longtime professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Jeff: I know the story is that Dr. Bose was on a plane with headphones and couldn’t hear his music, or couldn’t hear it very well. And kind of sketched out the principles of noise cancellation — was it on a napkin?

Dan: Probably not a napkin! (Laughs.)

But he sketched out the basic principles?

It was spring of 1978 and for those of us who are old enough to remember, way back in the 60s and 70s, the in-flight entertainment systems in airplanes had the speakers down in the armrest of the seat. And you used these hollow plastic flexible tubes with foam tips that you would press into your ear canals to get the sound from the speaker up to your ear, and the sound quality wasn’t very good. You had all these resonances from that tube.

And this is ‘78, so this is about the time the original Sony Walkman was introduced, along with Walkman style headphones. So some airlines were starting to use electrodynamic headphones like that.

The old-school foamies!

Yep. And Dr. Bose was excited — he got on a plane, and he saw that these different headphones were going to be used. But they didn’t block out any noise! When he turned the music up loud enough to hear it, it was all distorted. And so he started thinking about how to solve this problem, and he pulled out one of those 8.5 x 11” yellow pads and started scribbling equations. And that’s where he came up with the first idea.

1980 — Dan begins his work at Bose

In the spring of 1980, Bose needed to hire an electric engineer for their fledgling noise-cancelling headphones project. Dan was a student at nearby MIT, an institution that continues its strong ties with Bose Corporation to this day. "I was hired fresh out of school," said Dan. "I actually hadn’t quite finished my Master’s degree when I came here from MIT."

Here's a recent photo of Dan testing the Bose A20 aviation headset in flight, so he can speak authoritatively with fellow aircraft operators.

Jeff: So that was ’78 and you started in 1980. You were still a student at MIT, right?

Dan: Yeah, so [after that flight] Dr. Bose came back to the office and had one [in-house] engineer work on it. That engineer concluded after a few months that it wouldn’t work, so Dr. Bose hired another engineer named Roman Sapiejewski. Roman primarily had an acoustics background.

My background was not in acoustics, or music or anything like that. My background was in…the technical term is “feedback control systems” and “analog circuit design.” That was the skill they needed. So they hired me to work with Roman on these early prototypes.

Did you have Dr. Bose as a professor?

Actually, no. Of the MIT people here, I’m probably an odd case. I never took his class, which I regret in hindsight — I’ve learned a lot of it on the job. I never met the man [at MIT]. I interviewed with the company on a lark — I didn’t want to leave the Boston area, I saw they were interviewing, I signed up. And I was fascinated with the people I met and how deeply they thought about problems. I came here thinking I’d work here two or three years, learn a few things, then go back and get my PhD, but I fell in love with the place and never left.

And that was the same building back then — The Mountain?

Yep! We’d been in the building on The Mountain for about 5 years when I joined the company.

Are you from the Boston area originally?

No. My father was in the military, the Army. He was an Armor Officer, so I grew up all over the Eastern part of the U.S. mainly, a little time in Germany. And that proved useful later on when we got into doing products for military and aviation, because I was comfortable talking to people in uniform…I knew their life.

1981 to early-1986: "We traveled from base to base."

These days, Bose noise-cancelling headphones are as popular with pilots as they are with passengers. And the earliest prototypes Bose developed were, in fact, aviation headsets. But Dan and Roman learned quickly that securing a contract for military and aviation use would not be an easy task.

Jeff: Did you take the noise-cancellation technology to the military first?

Dan: Well by 1981, we had a working prototype that was doing pretty well from an active noise cancellation perspective. And Dr. Bose had this original vision of creating a headphone for use on airplanes, working with airline partners — as we did decades later. But when we estimated how much it would cost for us to make these headphones, and the price we’d have to sell them for? Our marketing folks said, “have a nice day….we don’t know how to sell this product, it’s going to be too expensive.”

This early Bose aviation headset prototype was used in the 1986 Voyager flight around the world, and is on-display at Bose Corporate headquarters.

Oh man, so you were on your own?

Roman and I were both passionate about [our noise-canceling headphones]. We knew we had something here. Dr. Bose knew we had something, he was supportive.

So we started thinking about other things we could do with the technology. And using active noise reduction to help people communicate in challenging, noisy environments where communication is critical seemed like an obvious ‘other’ application. At the time, Ronald Reagan was in the White House, and there was a lot of spending on military, so we thought “Oh great, we’ll talk to the Air Force, the Navy, the Army, and that’ll be our first customer.”

So from 1982 to ’85, or early ’86 we tried to make that happen. We built a lot of prototypes, we learned a few things, and we improved it. Then we traveled all around. In 1984 and ’85, I was at Patuxent River Naval Air Station in Maryland as prototypes were flown in helicopters. I was at Edwards Air Force base and they were flown in F15s. Finally, after all that work, we got this big contract. And it was canceled in early ’86 because of the cost and feature-set challenges for the larger digital intercom system that our headsets were supposed to connect to.

Late 1986: Bose noise-cancelling headphones on the Voyager flight around the world

On December 14, 1986 The Rutan Model 76 Voyager took off from Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert to much fanfare and press. It landed nine days later and became the first aircraft to fly around the world without stopping or refueling. Pilots Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager spent those nine days inside a 7-1/2’x 2’ cockpit/cabin described as a “horizontal telephone booth,” taking turns flying and sleeping. And the plane’s dual engines were basically right on top of them, causing vibration and noise that reached up to 110 decibels.

In their book, Voyager, Jeanna described the noise on earlier test flights: “It was debilitating; it’s the aural equivalent of those intense lights they shine in prisoners’ eyes in the movies…the prisoners always break.”

Luckily, they met Dan and Roman from Bose. The prototype Bose noise-cancelling headsets were ultimately credited with saving the pilots’ hearing, and helped Bose earn a reputation in the aviation field that still carries on through today. But as I found out from Dan, there was much more to the story.

In fall 1986, Dan and Bose RF engineer Mark Dinsmore (pictured) spent weeks preparing the Bose headset for the Voyager aircraft (in background). From Mr. Gauger's personal collection.

Jeff: So how did you guys get involved with the Voyager flight?

Dan: Well, we had been thinking about private pilots and general aviation. And just by chance that summer, we heard about the Voyager project. And we introduced ourselves to them and that led to some public acknowledgement of what we were doing and the rest is history.

I went way down the rabbit hole with the Voyager flight. I even picked up a copy of the book.

I have my copy here! And I’ve got photos I can send you from when that project was happening, because I spent about six weeks in Mojave, working on improving some things in that headphone for that flight.

OK, so you were there?

Oh yeah!

VIDEO: Working on the Voyager flight headset

Voyager pilot Dick Rutan writes glowingly of the Bose headsets in the book — “they were lifesavers,”— but things didn’t quite go as planned. In this video, Dan tells the entire fascinating story of pitching their headsets to the Voyager crew, improving the prototypes, and how humidity and human sweat caused a major problem.

And how did the pitch go? Were they just like 100% “OK, yeah, bring them in.” Because that’s kind of how it goes in the book.

(Shakes head.) It was interesting. We found out about the flight in early June of that year after they did a four-day test flight up and down the coast in California. A magazine article about the flight mentioned how noise was a problem, because they were using traditional aviation, passive-only headsets which clamp really hard around your ear. And I remember the article mentioning that the co-pilot, Jeana Yeager had physical bruises around both ears from wearing a headset four days straight.

So, my colleague Roman and I packed up two generations of prototypes — the ones that we had test-flown with the military and a new, improved one that was more comfortable. And we flew to LAX, we drove to Mojave. We got there mid-morning. We had no appointment — we basically made a salesman cold call on them. And we sat around the waiting room in their hangar for like 3, or 4 hours until we could get some time with them.

Oh wow!

We get ushered into a room with Dick Rutan, the retired, very experienced AirForce fighter pilot and test pilot. And Jeana Yeager, his partner and co-pilot. They basically say, “OK, tell us what you got, you got five minutes...we have to get back to work on the airplane.”

So we walked out of the hangar and went up to a Cessna 172, I think it was, that probably belonged to Dick. And Jeanna climbed into one seat and he climbed into the other. I was standing there with the open door, holding the [noise-canceling] electronics. Which were not in the headset at the time [they were in a separate, attached “box”]. And he fires up the airplane and then I point at the switch…he’s wearing the headset, he flips the switch, and he does a double-take. Then he turns it off and turns it back on. Dick shuts down the airplane, utters a few expletives and says, “We have to have this.”

And they decided it was mission critical. He had to fight his brother Burt, the designer of the airplane, to take this extra weight — because every [single] pound counted on that airplane. And Dick said, “No. We have to have this.”

Dan spent six weeks in fall 1986 at a hangar in the Mojave desert preparing the headsets for flight. Photo by Mark Greenberg, whose Voyager images are currently archived at Texas A&M University-Commerce Libraries.

They let you guys in!

Yes. They wanted the new, more comfortable design and we'd only ever built two of that version at that point. And they had all sorts of problems with them. Because, this is prototype hardware! This isn’t production hardware. And they have radios at every frequency you can imagine in this airplane.

So end of September, I fly out there with a good RF engineer who worked for Bose, and a footlocker full of equipment. And we started opening up the headphones, changing things, trying to fix this and that. He spent about a week and a half with me, then he had to go back to Boston. I spent 3 or 4 weeks out there just trying to get the headphones to work, until they finally worked well enough with all those radios. And then we were good to go.

1989 to Mid-90s: Bose aviation headsets take off

There was a long period of time between the Voyager flight and when the original QuietComfort headphones — Bose’s first consumer noise-cancelling headphones — arrived at Crutchfield in March 2001. The press that Bose received from the historic flight helped them finally launch their noise-cancelling aviation business.

But Dr. Bose's original vision always loomed large.

Jeff: So from the Voyager, what was the path to consumer headphones?

Dan: The Voyager flight was in ’86, and we got a lot of attention early ’87. So we decide that we’re going to develop an aviation headset, which we introduce in ’89. It was the first commercially available noise-cancelling headset.

Our founder and CEO Bill Crutchfield — who was in the same Consumer Electronics Hall-of-fame class as Dr. Bose — actually received a prototype of those. We searched for them, but couldn’t find them anywhere.

So Bill is a pilot?

Yes, Bill served in the Air Force and has been an experienced pilot for over 50 years.

Oh excellent. So here is the same generation headset. (Pulls out a first-generation Bose noise-cancelling headset.) I know this is the first-gen because — we’re going to reveal our secrets a little bit here — the inner earcup is clear and you can see the microphone.

The microphone had a little resistor on it to heat it up, to drive humidity away after our experience on the Voyager.

Dan shows me the circuitry inside a prototype for a first-generation Bose noise-cancelling aviation headset (from roughly 1989).

So you guys weren’t going to let that happen again. (Laughs.)

Right…so by the early 90s, we had a contract that had us sell a different version for some Air Force applications. And we won a large contract that has led us to be the primary supplier for headsets in armored vehicle use in the U.S. military and in a number of other militaries.

So that occupied us until the mid-90s. But all the time, we wanted to get back to doing a headphone for consumers — what Dr. Bose originally imagined.

We found the Bose Aviation headset II that Bill Crutchfield used in his Beechcraft King Air C90B in the '90s.

You stayed focused on that?

Yes, but we didn’t know how to make a headset at low enough cost. And we didn’t have the right balance of comfort, passive, and active noise-cancellation for consumer use — like we discussed earlier. Our earcups were a little too big and the design was [geared toward noise cancellation above all else].

I’ll give you a little bit of technical background: A noise-cancelling headphone has to make as much sound as it’s trying to cancel. Airplanes can be very loud at low frequencies and helicopters are even more brutal. And so we needed to develop headphones with small, lightweight earcups that could still make a lot of low-frequency sound.

It took a breakthrough of what we called TriPort technology. And that’s something Roman and Bob Maresca — now our Chairman of the Board here at Bose — came up with, originally for the Aviation headset X. I’ve had it here in this drawer for about 5-10 years. (Pulls out the Bose Aviation headset X from his desk.)

The original Bose QuietComfort headphones first appeared in the Crutchfield catalog in Summer 2001 (index page shown).

And that became sort of the "missing link" between aviation headsets and the original QuietComfort headphones?

This headset, because of Triport technology was close to half the weight, half the clamping force on your head, and more [noise-cancelling] performance than anything we’d ever done before. And it was that invention which enabled us to do the first QuietComfort headphones.

So as soon as we had this in market, Roman and Bob figured out a way to make headphones at a low enough cost, apply TriPort technology, and just optimize it around the frequent-flyer consumer application. So it took their breakthrough of figuring out how to balance active, passive, and comfort for the QuietComfort headphones to exist.

VIDEO: Working with Dr. Bose

While Bose, the company, was searching for that perfect balance, Dr. Bose personally preferred the scales tipped toward “quiet” above all else. So he didn’t mind using the aviation headsets, even for listening to music. The Aviation 10 headset Dan showed me actually belonged to Dr. Bose.

He had the engineers modify it and add a traditional headphone plug, so he could connect it to his audio gear. Perks of the job! In this video, Dan shares his fond memories of working directly with Dr. Bose.

Measurements vs perception: the Bose design philosophy

Before this interview, I watched a lecture where Dan discussed the idea of “measurements vs. perception” when creating headphones — or any audio gear. Dan’s point was that you couldn’t overvalue objective measurements taken in a lab, using microphones and other instruments. Sometimes, those measurements clash with how you and I experience something in the real world.

I emailed Dan ahead of time to let him know that this was something I wanted to discuss. But I admitted — there were parts of it I found hard to grasp!

Jeff: So I understand the difference between what you call “measurements” and “perception.” But it is hard for me to see how you tackle that problem from your end. Because perception seems like such an abstract or subjective thing.

Dan: Well, when I saw you wanted to talk about that, I was delighted. Because it is one of the things I’m most passionate about. And that question goes back to the very roots of Bose Corporation. Dr. Bose, in his acoustics course at MIT for years, would have a lecture or two on psychoacoustics, which is a branch of psychophysics, which is the study of how human beings and our brains — and our senses — perceive things.

And it’s easy to say “aww, perception, that’s just subjective.”

I don’t like the word ‘subjective’ there, because it leads you to believe that it’s all about how you feel about something. But, perception is as objective as the physical world of frequencies, measured in Hz and sound levels and dB SPL. It’s just that the instrument is different. The instrument is our brain and our sensory system, not the oscilloscope and spectrum analyzers.

Sorry!

(Laughs.) Oh no, everybody says it.

So for lack of a better way of asking — is there a way to measure perception?

It is harder to measure. But it is objective. It’s not subjective vs objective, it’s the difference between physical and perceptual. I’ll give you an example: probably the simplest perceptual test that most people have ever experienced, the most common one, is…have you ever been to the doctor, an audiologist to have your hearing checked?

Yep.

That’s an objective measure, perceptual test. You’re measuring the threshold of the quietest sounds that your ears can just detect. So that’s a psychophysical measurement of your hearing. And so, let me tie this back to what Dr Bose would talk about in his lectures:

The challenge is figuring out to measure what matters. And what matters is, what people hear. Not what you can measure with a spectrum analyzer. So the challenge is how do you take human beings, and ask them the right questions, and design experiments, so that you can measure their perception of some experience.

VIDEO: Dan explains how Bose tests noise cancellation

In this clip, Dan further explains the idea of physical measurements vs. perspective when testing noise cancellation. He told me that occasionally he and his fellow engineers will get so focused on a physical measurement, that they forget about the overall experience. For example, they'll drive up the active noise cancellation at a certain sound frequency, and lose sight of what's going on at other frequencies.

It becomes a difficult balancing act.

The present and future of Bose noise cancellation

The Bose QuietComfort Earbuds are a great example of how noise cancellation technology has evolved since Dan started over 40 years ago. For years, it was about absolute quiet and reducing lower frequencies. These days, noise cancellation is as much about control.

By tapping a button or using an app on your phone, you can decide how much noise to let in. You can even use the headphones’ built-in mics to pick up external sounds or focus on voices. And it’s no longer just about enjoying music! Bose now makes several “hearable” tech products that can help you sleep, boost hearing, and much more.

Jeff: You mentioned the stuff you can do with software. Is that the big difference from back in the day?

Dan: It has evolved. Every few years, I hear about some start-up company who thinks they’ve got the latest signal processing algorithm or the latest chip that’s going to completely change noise canceling. At the core, it’s a physics problem, it’s an acoustics problem. It’s “how well can we sense the sound that’s going down your ear, and influence it and control it.”

So for years, the work was dominated by acoustics and mechanical. The circuitry was all analog, because it has to be super-fast. We can’t tolerate much time delay from when the microphone says, “This is what’s going on,” and processing it, and putting it into the speaker, the driver to do the cancellation. Digital systems just weren’t that fast for us. [Or at least] high-audio-quality digital systems weren’t [back then]. So, it was analog circuitry for years. And you can’t get very fancy with analog circuitry.

It wasn’t until we went digital with QuietComfort 20 headphones, in 2013. That’s when we found a way to do all the processing we need — from time delay, to microphone signal, to speaker signal, measured in a few microseconds, that we could do in the software world.

Bose made front-page news in 2016 with the release of their first wireless noise-cancellers, the best-selling QuietComfort 35 headphones.

That’s where more of the refinements have happened?

Yes, since then, it’s been a question of “What’s worth doing?” What’s important to do? What’s meaningful to do? What matters?

In QC 20, we had the ability to flip a switch to take you from “Aware mode” near-transparency to lots of cancellation. In QC 30, that became controllable cancellation where you essentially have a volume control on the world. And that carried over into the Noise Cancelling Headphone 700s and the QC earbuds. But there’s more to come in the future. You know, it’s about giving you control over how you hear the world.

Well I won’t ask you to spoil anything! But before we stop, I just want to ask about your philanthropic work with hyperacusisresearch.org. Did you run across this rare hearing disorder in your research?

They actually reached out to us. And I just listened to their concerns and try to look for ways that maybe our headphones can help. Or the things we can do to tune the software to make them beneficial to them. And we’ve donated headphones to these organizations, and there’s actually a program we have [at soundsanctuary.bose.com].

I think it's very admirable...and not plastered all over your website, like “look at us.” I know you guys are in a unique position to help, so I think it’s really cool.

Well I appreciate hearing that. I came to Bose in kind of an unusual path. I’m not a musician. I wasn’t a student of Dr. Bose’s at M.I.T. I’ve always loved music, I had a great sound system as a student and I’ve got, you know, 12 feet of vinyl stacked in a shelf somewhere at my home. But I’ve always felt that this technology helps in ways beyond helping people enjoy their music in loud places. That’s what drew me to the aviation and military applications, where we’re helping people protect their hearing. And understand critical communications that can save lives.

I’ve always been drawn to these applications that really matter, in bigger ways. So when people reach out I want to talk to them…I want to see what we can do to help.

Well, Dan, thank you so much for your time. And thanks to Team Bose for working with us to make this happen. I hope you enjoyed this as much as I did.

Yes, thank you. This was fun!

BONUS VIDEO: Bose's legendary "Reverb Room"

I've heard so many stories about the "Reverb Room" at Bose HQ, that I had to ask Dan about it. Kind of the opposite of an anechoic chamber (they have those too), the sound reflections in this room are out of control. How better to test noise-cancelling headphones than to have noise swarming from all directions?

Samir from Mount Laurel, NJ

Posted on 1/26/2021

Great interview, Jeff! I came to this article after listening to the associated podcast. It was fascinating to hear Dan's insight into the development process! I'm a fan of Bose's noise-cancelling headphones, and own two of them (QuietComfort 25, which I use at the office, and QuietComfort 35, which I use at home).

Jeff Miller from Crutchfield

on 2/5/2021

DaveB from Charlottesville, VA

Posted on 10/20/2020

Epic interview, Jeff! I thought I knew everything there was to know about headphones, but I learned quite a bit from this article. :-) Thank you for doing this.

Jeff Miller from Crutchfield

on 10/21/2020